archiv-foto: christof graf/ Laeiszhalle; früher: Musikhalle, Hamburg

Gedanken zum Leonard Cohen Tribute-Konzert an einem historischen Ort

von MIchael Brenner

1970 spielte Leonard Cohen zum ersten Mal in Deutschland und in Europa. Der Ort: die historische Musikhalle in Hamburg, ein neobarockes Konzerthaus. Ich war damals ich ein 18-jähriger Junge auf dem Weg zum Abitur.

Im Rückblick aus dem Jahr 2026 beschreibt Künstliche Intelligenz das Jahr 1970 mit folgenden Sätzen: Das Jahr 1970 markierte den Beginn eines turbulenten Jahrzehnts, geprägt von Ost-West-Annäherung durch Willy Brandts Politik, dem Höhepunkt des Vietnamkriegs, der Apollo-13-Mission und dem Zerfall der Beatles. Kulturell dominierten Schlaghosen, Plateauschuhe und der aufkommende Umweltschutz. Es war ein Wendepunkt für massive soziale Umbrüche und den Generationenwechsel.

Wir schreiben das Jahr 2026. Die Welt ist eine andere geworden. Dass sie besser und schöner geworden ist, wie Viele meiner Generation 1970 erhofften, kann ich nicht sagen. Vor fast zehn Jahren ist Leonard Cohen im November 2016 verstorben. In der Gegenwart bin ein alter Mann von 74 Jahren.

Der 23. Januar 2026 ist ein eiskalter Winterabend und ich besuche mit einem Freund das Leonard Cohen Tribute-Konzert der Gruppe Field Commander C. in der Laeiszhalle. Es ist die frühere Musikhalle am Johannes-Brahms-Platz (früher: Karl-Muck-Platz) unter neuem Namen und gehört heute zur Elbphilharmonie. Im Jahr 1968 fand in der Musikhalle die feierliche Veranstaltung zu meiner Jugendweihe statt, die ich schon lange vergessen hatte. In dem alten Verwaltungsgebäude gegenüber erlebte ich Ende 1970 meine Verhandlung als Kriegsdienstverweigerer.

Das Leonard Cohen Tribute Konzert war vom Veranstalter angekündigt als „eine Hommage an den großen, kanadischen Singer-Songwriter Leonard Cohen und eine der eindrucksvollsten Cohen-Live-Shows, die Deutschland zu bieten hat. Neben der großen Formation, die sich ausgiebig der legendären Tour von 1979 widmet und bundesweit in den renommierten Konzerthäusern für Gänsehaut und minutenlange Standing Ovations sorgt, geht Rolf Ableiters Field Commander C. nun mit intimerer Besetzung auf Spurensuche. »Leonard Cohen’s Early Works – the Roots of Hallelujah« ist der Titel des neuen Programms.

Wer sich mit Leonard Cohen beschäftigt, kommt um den Song »Hallelujah« nicht herum. Wenn man aber verstehen möchte, wie dieser unglaubliche Song entstehen konnte, muss man sich mit dem Frühwerk Cohens auseinandersetzen. Songs wie »Suzanne«, »Bird on the Wire«, »So Long Marianne«, »Famous Blue Raincoat«. sind neben »Hallelujah« mit die berühmtesten Werke Cohens und entstanden alle in der Schaffenszeit der ersten vier Alben. Die Gäste erwartet ein Abend voller Melancholie, Poesie, virtuoser Spielfreude und Geschichten rund um sein grandioses Frühwerk – gefühlvoll interpretiert mit Gitarre, Violine, Cello, Orgel und Akkordeon.“

Für mich und für Leonard Cohen-Fans ist der Veranstaltungsort Musikhalle ein historischer Ort. Hier hat Leonard am Anfang seiner Karriere am 4. Mai 1970 sein erstes Konzert in Deutschland und in Europa gegeben. Fast genau 55 Jahre später treten Rolf Ableiter und Field Commander C. mit ihrem Tribute-Konzert am selben Ort auf.

1970 traten wenige Wochen vor Leonard Cohen gemeinsam Judy Collins und Tom Paxton am selben Ort auf. Judy Collins, zur Erinnerung, war diejenige Folksängerin, die ganz wesentlich zum Start von Leonard Cohen Cohens Karriere beigetragen hat. Das Konzert von Judy Collins und Paxton habe ich damals besucht, zu Leonard bin ich leider nicht gegangen. Bis heute bedauere ich es sehr.

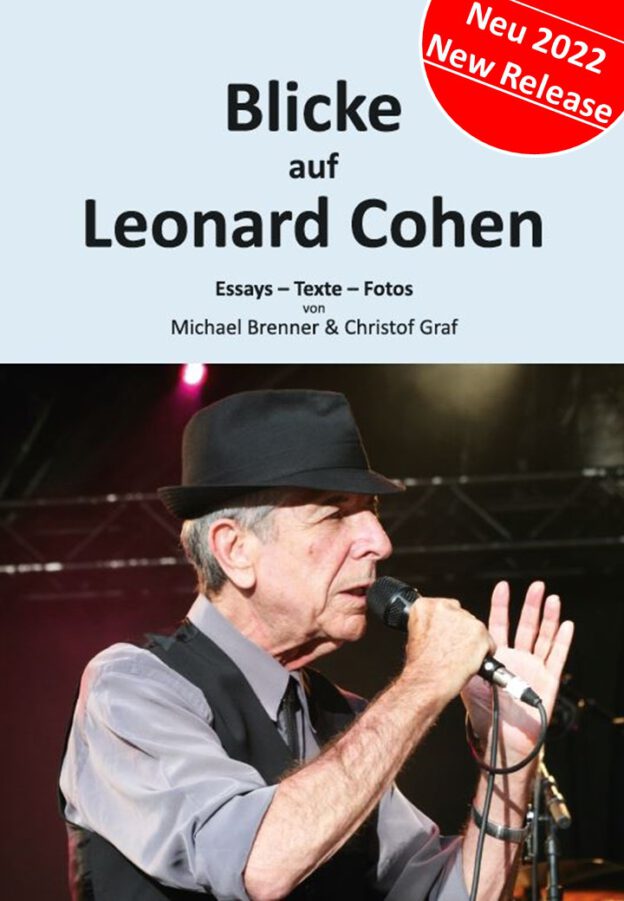

Das Leonard Cohen-Konzert von Mai 1970 wurde von dem legendären Fotografen Günter Zint mit zahlreichen Fotos dokumentiert. Diese wurden vor einigen Jahren mit Zints Zustimmung in dem Buch »Blicke auf Leonard Cohen« von Christof Graf und Michael Brenner veröffentlicht.

Drei Monate später, im August 1970, ist Leonard Cohen dann beim Open Air Festival auf der Isle of Wight aufgetreten. Statt der erwarteten 30.000 oder 40.000 Zuschauer kamen nach Schätzungen mehr als eine halbe Million Menschen. Die Organisation war dem nicht gewachsen und die Stimmung wurde aggressiv, auch gegen die Künstler. Doch Leonard Cohen gelang es mit seinem legendären nächtlichen Auftritt, die wütenden Festival Teilnehmer zu beruhigen und friedlich zu stimmen.

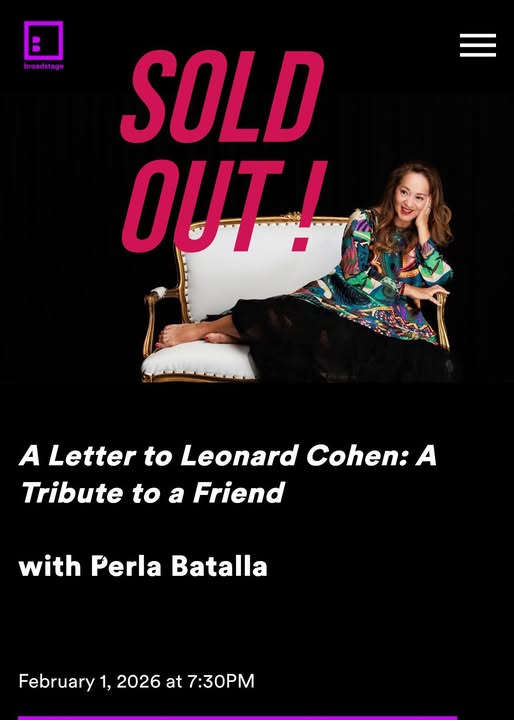

Das Tribute Konzert 2026 von Rolf Ableitner und Field Commander C. brachte den Besuchern einen schönen Abend. Die Veranstaltung war bis auf wenige Restplätze ausverkauft. Mir hat es sehr gefallen und dem Rest Zuschauer ganz offensichtlich auch. Sie waren begeistert. Zwischen den einzelnen Songs gab Rolf Ableiter jeweils Erläuterungen zu Leonard Cohen und dem nachfolgenden Song. In Hamburg erwähnte er auch Judy Collins und erzählte die Vorkommnisse von der Isle of Wight.

Zwei Songs ragten an diesem Abend für mich heraus, Sisters of Mercy und Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye, ohnehin zwei meiner Lieblingssongs.

Bei YouTube sind viele Konzert-Ausschnitte der Gruppe Field Commander C. zu finden. Es lohnt sich, sie sich anzusehen.