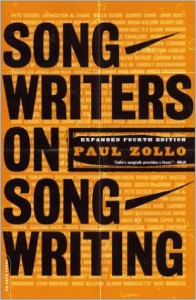

Paul Zollos Buch, indem Songwriter (wie z.B. Bob Dylan und Leonard Cohen über die hohe Kunst des Songwriting referieren, gibt es nun schon in der vierten auch erweiterten Auflage. In der neuen Ausgabe mit dabei – neben Dyaln und Cohen – auch Lou Reed und Lenny Kravitz.

This expanded fourth edition of Songwriters on Songwriting includes ten new interviews–with Alanis Morissette, Lenny Kravitz, Lou Reed, and others. In these pages, sixty-two of the greatest songwriters of our time go straight to the source of the magic of songwriting by offering their thoughts, feelings, and opinions on their art. Representing almost every genre of popular music, from blues to pop to rock, here are the figures that have shaped American music as we know it.

Bob Dylan on Sacrifice, the Unconscious Mind, and How to Cultivate the Perfect Environment for Creative Work

“People have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms them.”

By Maria Popova

Van Morrison once characterized Bob Dylan (b. May 24, 1941) as the greatest living poet. And since poetry, per Muriel Rukeyser’s beautiful definition, is an art that relies on the “moving relation between individual consciousness and the world,” to glimpse Dylan’s poetic prowess is to grasp at once his singular consciousness and our broader experience of the world. That’s precisely what shines through in Paul Zollo’s 1991 interview with Dylan, found in Songwriters On Songwriting (public library) — that excellent and extensive treasure trove that gave us Pete Seeger on originality and also features conversations with such celebrated musicians as Suzanne Vega, Leonard Cohen, k.d. lang, David Byrne, Carole King, and Neil Young, whose insights on songwriting extend to the broader realm of creative work in a multitude of disciplines.

Zollo captures Dylan’s singular creative footprint:

Pete Seeger said, “All songwriters are links in a chain,” yet there are few artists in this evolutionary arc whose influence is as profound as that of Bob Dylan. It’s hard to imagine the art of songwriting as we know it without him.

[…]

There’s an unmistakable elegance in Dylan’s words, an almost biblical beauty that has sustained his songs throughout the years.

One essential aspect of Dylan’s creative process that comes up again and again in the interview is the notion of the unconscious and the optimal environment for its free reign. Dylan tells Zollo:

It’s nice to be able to put yourself in an environment where you can completely accept all the unconscious stuff that comes to you from your inner workings of your mind. And block yourself off to where you can control it all, take it down…

Like many creators, Dylan values that unconscious aspect of creativity far more than rational deliberation, speaking to the idea that the muse cannot be willed, only welcomed — a testament to the role of unconscious processing in the psychological stages of creative work. He tells Zollo:

The best songs to me — my best songs — are songs which were written very quickly. Yeah, very, very quickly. Just about as much time as it takes to write it down is about as long as it takes to write it.

In order to do that, he adds, one must “stay in the unconscious frame of mind to pull it off, which is the state of mind you have to be in anyway.” Contrary to Bukowski’s punchy assertion that the ideal environment for creativity is an irrelevant delusion and E.B. White’s admonition that “a writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper,” Dylan believes this optimal frame of mind can be induced — or, at least, greatly aided — by the right conditions:

For me, the environment to write the song is extremely important. The environment has to bring something out in me that wants to be brought out. It’s a contemplative, reflective thing…

Environment is very important. People need peaceful, invigorating environments. Stimulating environments.

To foster such unconscious receptivity, Dylan argues that “you have to be able to get the thoughts out of your mind” and explains:

First of all, there’s two kinds of thoughts in your mind: there’s good thoughts and evil thoughts. Both come through your mind. Some people are more loaded down with one than another. Nevertheless, they come through. And you have to be able to sort them out, if you want to be a songwriter, if you want to be a song singer. You must get rid of all that baggage. You ought to be able to sort out those thoughts, because they don’t mean anything, they’re just pulling you around, too. It’s important to get rid of them thoughts.

Then you can do something from some kind of surveillance of the situation. You have some kind of place where you can see it but it can’t affect you. Where you can bring something to the matter, besides just take, take, take, take, take. As so many situations in life are today. Take, take, take, that’s all that it is. What’s in it for me? That syndrome which started in the Me Decade, whenever that was. We’re still in that. It’s still happening.

Dylan makes a seemingly controversial statement that resonates with new layers of poignancy in our present age of seemingly infinite cloud libraries of streamable music and a constant, industrialized churning out of disposable pop hits:

The world don’t need any more songs… As a matter of fact, if nobody wrote any songs from this day on, the world ain’t gonna suffer for it. Nobody cares. There’s enough songs for people to listen to, if they want to listen to songs. For every man, woman and child on earth, they could be sent, probably, each of them, a hundred songs, and never be repeated. There’s enough songs.

Unless someone’s gonna come along with a pure heart and has something to say. That’s a different story.

But as far as songwriting, any idiot could do it… Everybody writes a song just like everybody’s got that one great novel in them.

In fact, Dylan seems to regard “popular entertainers” — despite counting himself among them — with a certain degree of contempt and mistrust:

It’s not a good idea and it’s bad luck to look for life’s guidance to popular entertainers.

Dylan considers what it takes to be among the few rare exceptions worthy of true creative respect:

Madonna’s good, she’s talented, she puts all kinds of stuff together, she’s learned her thing… But it’s the kind of thing which takes years and years out of your life to be able to do. You’ve got to sacrifice a whole lot to do that. Sacrifice. If you want to make it big, you’ve got to sacrifice a whole lot.

When Zollo asks Dylan whether he sees himself the way Van Morrison famously characterized him, Dylan replies:

[Pause] Sometimes. It’s within me. It’s within me to put myself up and be a poet. But it’s a dedication. [Softly] It’s a big dedication.

[Pause] Poets don’t drive cars. [Laughs] Poets don’t go to the supermarket. Poets don’t empty the garbage. Poets aren’t on the PTA. Poets, you know, they don’t go picket the Better Housing Bureau, or whatever. Poets don’t… poets don’t even speak on the telephone. Poets don’t even talk to anybody. Poets do a lot of listening and … and usually they know why they’re poets! [Laughs]

[…]

Poets live on the land. They behave in a gentlemanly way. And live by their own gentlemanly code.

[Pause] And die broke. Or drown in lakes. Poets usually have very unhappy endings…

When the conversation veers into the question of whether Shakespeare was really Shakespeare and people’s skepticism about accepting that a single person was able to produce such a body of work, Dylan makes a remark that extends to a great many more aspects of society:

People have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms them.

He seems especially dismissive of public opinion and even more so, similarly to David Bowie, of artists’ preoccupation with it:

It’s not to anybody’s best interest to think about how they will be perceived tomorrow. It hurts you in the long run.

As the conversation progresses, Zollo returns to songwriting, citing Pete Seeger’s assertion that originality is a myth and all songwriters are “links in a chain,” to which Dylan responds:

The evolution of a song is like a snake, with its tail in its mouth. That’s evolution. That’s what it is. As soon as you’re there, you find your tail.

Considering his own songs, Dylan contemplates their nature, the self-transcendence necessary for writing, and the creative value of being an outcast:

My songs aren’t dreams. They’re more of a responsive nature…

To me, when you need them, they appear. Your life doesn’t have to be in turmoil to write a song like that but you need to be outside of it. That’s why a lot of people, me myself included, write songs when one form or another of society has rejected you. So that you can truly write about it from the outside. Someone who’s never been out there can only imagine it as anything, really.

###

Leonard Cohen on Creativity, Hard Work, and Why You Should Never Quit Before You Know What It Is You’re Quitting

“The cutting of the gem has to be finished before you can see whether it shines.”

By Maria Popova

Canadian singer-songwriter, poet, and novelist Leonard Cohen (b. September 21, 1934) is among the most exhilarating creative spirits of the past century. Recipient of the prestigious Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and countless other accolades, and an ordained Rinzai Buddhist monk, his music has extended popular song into the realm of poetry, even philosophy. By the time Bob Dylan rose to fame, Cohen already had several volumes of poetry and two novels under his belt, including the critically acclaimed Beautiful Losers, which famously led Allen Ginsberg to remark that “Dylan blew everybody’s mind, except Leonard’s.” Once he turned to songwriting in the late 1960s, the world of music was forever changed.

leonardcohen

From Paul Zollo’s impressive interview compendium Songwriters on Songwriting (public library) — which also gave us Pete Seeger on originality, Bob Dylan on sacrifice and the unconscious mind, and Carole King on perspiration vs. inspiration — comes a spectacular and wide-ranging 1992 conversation with Cohen, who begins by considering the purpose of music in human life:

There are always meaningful songs for somebody. People are doing their courting, people are finding their wives, people are making babies, people are washing their dishes, people are getting through the day, with songs that we may find insignificant. But their significance is affirmed by others. There’s always someone affirming the significance of a song by taking a woman into his arms or by getting through the night. That’s what dignifies the song. Songs don’t dignify human activity. Human activity dignifies the song.

Cohen approaches his work with extraordinary doggedness reflecting the notion that work ethic supersedes what we call “inspiration” — something articulated by such acclaimed and diverse creators as the celebrated composer Tchaikovsky (“A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood.”), novelist Isabel Allende (“Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too.”), painter Chuck Close (Inspiration is for amateurs — the rest of us just show up and get to work.”), beloved author E.B. White (“A writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper.”), Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope (“My belief of book writing is much the same as my belief as to shoemaking. The man who will work the hardest at it, and will work with the most honest purpose, will work the best.”), and designer Massimo Vignelli (“There is no design without discipline.”). Cohen tells Zollo:

I’m writing all the time. And as the songs begin to coalesce, I’m not doing anything else but writing. I wish I were one of those people who wrote songs quickly. But I’m not. So it takes me a great deal of time to find out what the song is. So I’m working most of the time.

[…]

To find a song that I can sing, to engage my interest, to penetrate my boredom with myself and my disinterest in my own opinions, to penetrate those barriers, the song has to speak to me with a certain urgency.

To be able to find that song that I can be interested in takes many versions and it takes a lot of uncovering.

[…]

My immediate realm of thought is bureaucratic and like a traffic jam. My ordinary state of mind is very much like the waiting room at the DMV… So to penetrate this chattering and this meaningless debate that is occupying most of my attention, I have to come up with something that really speaks to my deepest interests. Otherwise I nod off in one way or another. So to find that song, that urgent song, takes a lot of versions and a lot of work and a lot of sweat.

But why shouldn’t my work be hard? Almost everybody’s work is hard. One is distracted by this notion that there is such a thing as inspiration, that it comes fast and easy. And some people are graced by that style. I’m not. So I have to work as hard as any stiff, to come up with my payload.

He later adds:

Freedom and restriction are just luxurious terms to one who is locked in a dungeon in the tower of song. These are just … ideas. I don’t have the sense of restriction or freedom. I just have the sense of work. I have the sense of hard labor.

When asked whether he ever finds that “hard labor” enjoyable, Cohen echoes Lewis Hyde’s distinction between work and creative labor and considers what fulfilling work actually means:

It has a certain nourishment. The mental physique is muscular. That gives you a certain stride as you walk along the dismal landscape of your inner thoughts. You have a certain kind of tone to your activity. But most of the time it doesn’t help. It’s just hard work.

But I think unemployment is the great affliction of man. Even people with jobs are unemployed. In fact, most people with jobs are unemployed. I can say, happily and gratefully, that I am fully employed. Maybe all hard work means is fully employed.

Cohen further illustrates the point that ideas don’t simply appear to him with a charming anecdote, citing a writer friend of his who once said that Cohen’s mind “is unpolluted by a single idea,” which he took as a great compliment. Instead, he stresses the value of iteration and notes that his work consists of “just versions.” When Zollo asks whether each song begins with a lyrical idea, Cohen answers with lyrical defiance:

[Writing] begins with an appetite to discover my self-respect. To redeem the day. So the day does not go down in debt. It begins with that kind of appetite.

Cohen addresses the question of where good ideas come from with charming irreverence, producing the now-legendary line that Paul Holdengräber quoted in his conversation with David Lynch on creativity. Cohen echoes T.S. Eliot’s thoughts on the mystical quality of creativity and tells Zollo:

If I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often. It’s a mysterious condition. It’s much like the life of a Catholic nun. You’re married to a mystery.

But Cohen’s most moving insights on songwriting transcend the specificity of the craft and extend to the universals of life. Addressing Zollo’s astonishment at the fact that Cohen has discarded entire finished song verses, he reflects on the necessary stick-to-itiveness of the creative process — this notion that before we quit, we have to have invested all of ourselves in order for the full picture to reveal itself and justify the quitting, which applies equally to everything from work to love:

Before I can discard the verse, I have to write it… I can’t discard a verse before it is written because it is the writing of the verse that produces whatever delights or interests or facets that are going to catch the light. The cutting of the gem has to be finished before you can see whether it shines.

Cohen returns to the notion of hard work almost as an existential imperative:

I always used to work hard. But I had no idea what hard work was until something changed in my mind… I don’t really know what it was. Maybe some sense that this whole enterprise is limited, that there was an end in sight… That you were really truly mortal.

Considering his ongoing interest in the process itself rather than the outcome, Cohen makes a beautiful case for the art of self-renewal by exploring the deeper rewards and gratifications that have kept him going for half a century:

It [has] to do with two things. One is economic urgency. I just never made enough money to say, “Oh, man, I think I’m gonna get a yacht now and scuba-dive.” I never had those kinds of funds available to me to make radical decisions about what I might do in life. Besides that, I was trained in what later became known as the Montreal School of Poetry. Before there were prizes, before there were grants, before there were even girls who cared about what I did. We would meet, a loosely defined group of people. There were no prizes, as I said, no rewards other than the work itself. We would read each other poems. We were passionately involved with poems and our lives were involved with this occupation…

We had in our minds the examples of poets who continued to work their whole lives. There was never any sense of a raid on the marketplace, that you should come up with a hit and get out. That kind of sensibility simply did not take root in my mind until very recently…

So I always had the sense of being in this for keeps, if your health lasts you. And you’re fortunate enough to have the days at your disposal so you can keep on doing this. I never had the sense that there was an end. That there was a retirement or that there was a jackpot.

Quelle:

https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/07/15/leonard-cohen-paul-zollo-creativity/

https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/05/21/bob-dylan-songwriters-on-songwriting-interview/